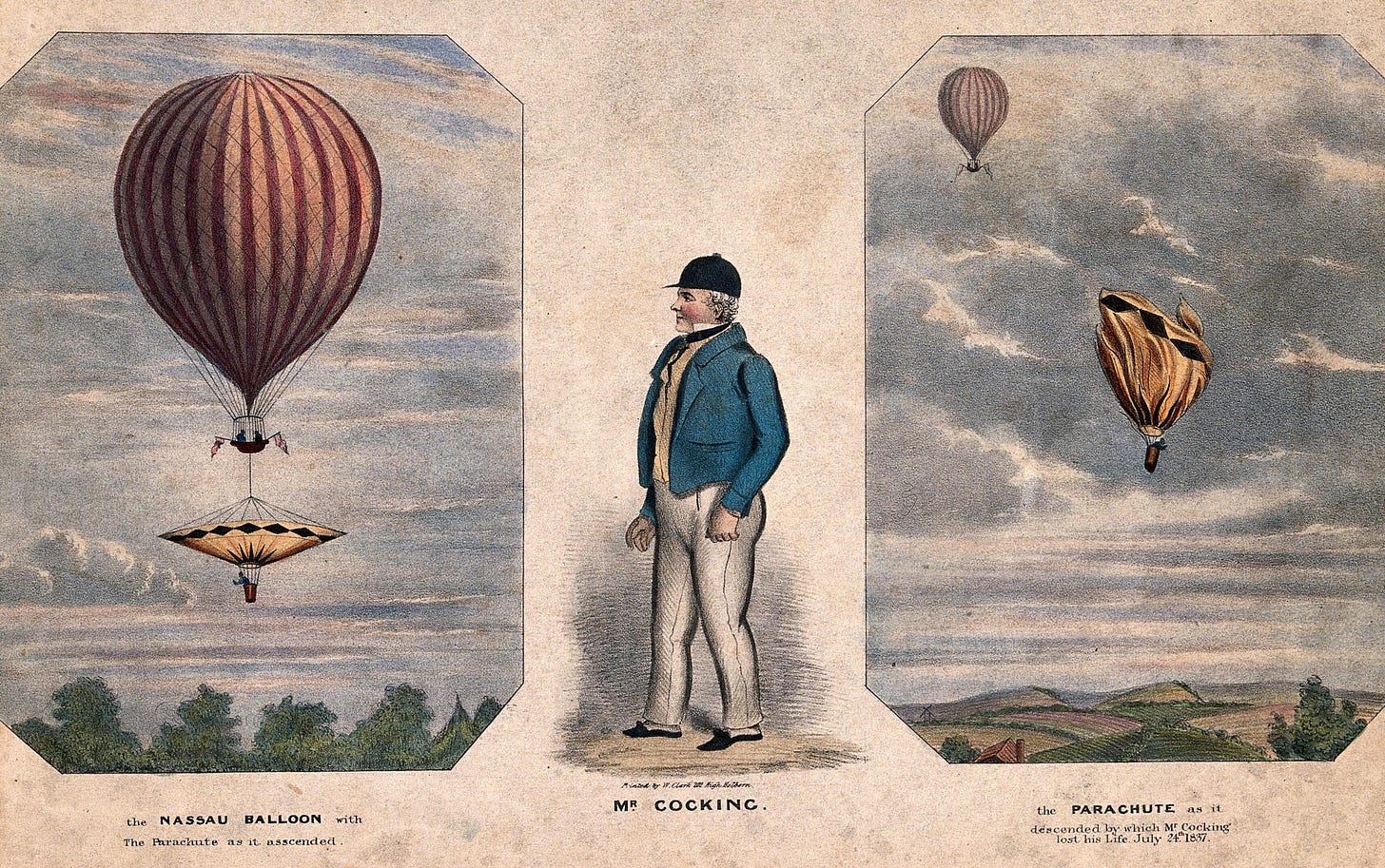

On July 24, 1837, British watercolourist and amateur scientist Robert Cocking ascended above Vauxhall Gardens in London in a hot air balloon. When he reached a height of approximately 1.5 kilometres, he jumped out. Years earlier Cocking had witnessed a successful parachute jump and the amateur scientist in him thought that he could improve upon the design of the parachute. He spent the next twenty years proving that thought. The ascent over Vauxhall Gardens was to be the first test of his new design. As he detached himself from the hot air balloon the ground far below would have looked like a stationary object a long way off, a destination never to be reached. That is the illusion of falling from great heights.

I remember a morning tea at an old workplace, a farewell for a director whose contract was not renewed. None of the people who had made the decision to terminate his contract were in attendance. It was just us underlings huddled around the supermarket cake and the snacks that we had all chipped in for and hurriedly bought after we realised that the executive refused to pay for a farewell morning tea. After standing around awkwardly, the condemned man, for that is what it felt like, gave a speech. And what I recall from that speech are two things. The first was that he had spent five years in that job and that he had just turned 50 years old. “That means I have spent ten percent of my life here,” he said, completing the math for us. There was real regret in his words. Yet the second thing I recall from that morning was me thinking that if his contract had not been cancelled, he would have happily stayed on for another ten years.

The workplace where that morning tea took place was the most toxic environment I have ever experienced. Harassment, bullying, nepotism, corruption, racism, negligence, incompetence – it had it all. And I knew all of this within the first six months of starting there. And yet, I stayed in that role for three and a half years, almost ten percent of my life at that stage. I did so for two reasons, and I still regret both.

About the time I started that job, I made a decision to take my writing seriously. The job allowed me plenty of time to work on my writing: mornings, evenings and weekends. It seemed like the perfect scenario – a steady income that would allow me to pursue my creative dream. But that is not how it worked out.

You cannot spend one third of your day, five days a week in a toxic environment and not have that affect you. It seeps into you – through the office gossip, through listening to the frustrations of colleagues, through watching colleagues breakdown in tears, through watching the inept gain promotion, by being continually undervalued. For eight hours a day I was swimming through a sea of mediocrity, but I convinced myself that I was the only one not getting wet. But I was wrong, I was drenched to the bone.

The evidence of that was borne out through my relationships with family and friends. I was angry, frustrated, tense, short with people. I was not well. So I made the decision to leave. And then stayed for another two years.

People that know me would likely describe me as a gregarious and confident person. But when I went to look around for a new job, whatever confidence I once had seemed to have evaporated. I don’t know when it left me or where it went to, but it was gone. I feared applying for jobs, I convinced myself that I would never get an interview, that I was unqualified, I was an embarrassment. The risks associated with leaving seemed greater than risks associated with staying. So, after taking the decision to leave, I did nothing. Nothing that is except make excuses why I was better off staying put. The money was good. The hours were few. There were some good people in the office. At least it allowed me time to write.

That was the biggest lie of all. Because every time I sat down to write I was angry, I was frustrated, I was tense. I was uncreative. The workplace had corroded me from within. It convinced me that the value it placed upon me was my true value. It convinced me that I had no other options than to continue. But worst of all it had destroyed the possibility of me doing the one thing I felt that I was meant to be doing; writing.

Looking back on that time, I believe that all of my unhappiness stemmed from one truth. That is, that while I was there, I was not dedicating myself 100% to what I was meant to do. I am not sure if everyone in life feels that there is something that they are meant to do. But I feel that. And what I feel is that I am meant to be writing. It gives me meaning, I value it. Regardless of how my writing is received (and there are plenty of publishers and editors who refuse to receive it at all!) when I finish a piece, I feel immense satisfaction.

I have never aspired to be anything. Not a lawyer, an engineer or a doctor. My aspirations have always involved doing something: travel, write a book, learn a language. We are already being something once we are born. We are being human, an exceedingly difficult task by itself; You have to wake when you'd rather sleep, stay put when you'd rather run, smile when you'd rather scream. Let’s all forget about being something. Let’s dedicate our time to doing something, something we love.

Let me be clear. I am not advocating that we should all quit our jobs. Work can, and should, be meaningful. It should add something to our lives. What I am advocating, is that if you do not feel fulfilled in your work, if you ascribe no value to what you do for one third of your day, if work is preventing you from doing what you are meant to be doing, then you should make a change. The work environments that we really need to get out of often convince us that that change can’t be made, but it can.

On that day over London way back in 1837, at some point Robert Cocking must have realised, with rising panic, that the earth was indeed rushing up at him. His parachute, twenty years in the making and weighing over 100 kilos, failed him. He was confronted with the reality of the Earth, and it was a meeting he did not survive. Whether we realise it or not, the Earth is rushing up at all of us; me who writes, you who read. We can do nothing about that. But we can decide how best to use the time that is left. Will we use it to make excuses, undervalue ourselves, fight the urge to change? Or will we find the courage to do the things that we know we are meant to do?

After writing this post I came across an episode of the podcast A Slight Change of Plans which looks at the science of quitting. Well worth a listen to understand what climbing Mt. Everest, playing poker and the Status Quo bias can tell us about when, how and why we should quit.