Today’s post does contain some coarse language. If you are ok with that, read on.

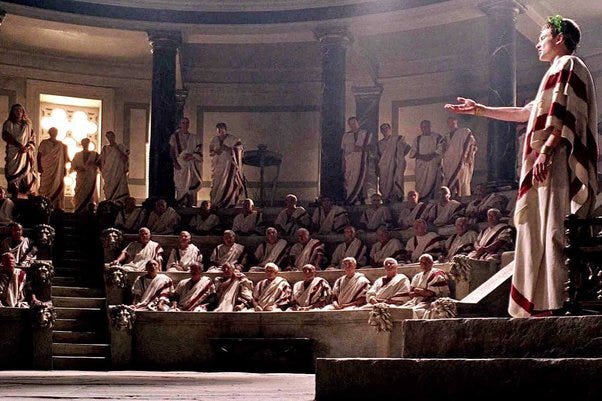

“The best argument against Democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.” Winston Churchill gets the credit for giving us this dim view of the west’s democratic tradition. Regardless of who did indeed say it, I have recently had the opportunity to put it to the test.

Part of the bargain of leaving steady work to try to make it as a writer in Australia is the obligation to accept any casual work you can find, if you are at all concerned with survival. Which is why I found myself manning the pre-polling election booths at Albion Park for one long week in late March. It was a chance to spend a few minutes with hundreds of voters.

My high-sounding role was the Declaration Voting Instruction Officer. I was dealing with the electors who were voting outside of their usual district, were enrolling to vote for the first time or were updating their enrolment details.

The first question I had to ask was, “Have you already voted in this election?” Kayne, 37, gave me a typical response. “You couldn’t pay me enough money to vote twice, mate.” I explained that talk of money was a moot point. “It’s illegal to vote twice,” I said, “so no matter how much I paid you, you wouldn’t be able to.” But Kayne was not to be swayed. “Yeah, but I wouldn’t anyway, even if you paid me.” And around we went.

I say Kayne’s answer was typical, but only amongst the men. Women simply answered “No”. I am not sure why this gender-based difference to such a simple question.

And it wasn’t the only difference. I noticed in the men a distinct distrust of authority, a distrust that was, if not absent in the female voters, at least mercifully unmanifested.

Kenneth, 63, refused to give back his pen after he had voted. When I insisted that his Bic be returned to the box to be sanitised and distributed to other voters, Kenny informed me that he “was a fucking taxpayer and he owned the fucking pen.”

Barry, 73, proudly told me he had numbered all the upper house candidates from 1 to 293. “Why would you do that?” I asked. “So some bastard has to count them all,” he said. I told him that they only counted the first two preferences. He didn’t seem to care.

When I asked Eric, 57, for his identification to prove he was in fact Eric and 57, his handlebar moustache bristled. “Is this fucking Long Bay gaol, mate?”

“No, sir,” I replied. “This is the Albion Park election centre. Are you meant to be someplace else?”

“Since when do you need to show ID?” he asked.

“Since 1901,” I said, though that was just a guess.

“I’m trying to vote mate, and you’re just trying to make it hard for me,” he said. I assured Eric that all I was trying to do was ensure he didn’t get fined. He said I could stick the vote up my arse. I told him that that would be considered an informal vote. Eric left without voting.

The fine for not voting in Australia is $55. I thought mentioning the fine would have helped as it seemed to be uppermost in other people’s minds. I’d never realised how powerful the threat of that fine was. Years ago, I tried to cast a vote at the Australian Embassy in Buenos Aires. The lady at reception asked me if I really wanted to vote. They had limited ballot papers available, and they were expecting the Wallabies* later in the day. She had been asked to make sure they had enough ballot papers on hand for them. I decided that I didn’t really want to vote and left. Being fined for not voting never crossed my mind. And I was never fined.

But for a nation of voters that are supposedly anti-authoritarian, there was a very real fear of being fined. Voters would ask me to turn around my computer so they could watch me click their names off the roll as having voted, others took photos of their completed vote to be used as proof, others filmed themselves dropping their votes into the ballot box.

Jennifer, 67, told me she didn’t know what her electoral district was. I asked her for her address. She didn’t have one. She told me she lived in her car. I asked her why she was making the effort to vote and not only vote, but vote early. “Don’t want to get fined.” But they’d never find you I said, you don’t have an address. She laughed at my ignorance. “They’ll get you,” she said. “They always do.”

But none of this shocked me. What shocked me was the amount of people who didn’t know the date (only one lady, Susan 37, had no idea what the election was even for, though she still voted). Now, is there an argument to be made that knowing the date should be a precondition of being able to vote? Maybe. I did note that nobody born in the 1930s (there were quite a few, how many elections had they been through I wondered) had any trouble with the date. I initially suspected that once in your nineties every day is accounted for, known and treasured.

Later, I concluded that knowing the date was not a question of intelligence. When people came to fill in the date they would immediately stop and their hands would go to their phones. I realised that the date is information that no longer has to be carried around in one’s head. It was to hand and that was enough.

The younger voters would fill in the date, and then almost immediately start to complain about the amount of paper being used. “You’re killing the environment” they told me. It was a fair point. Between the ‘how to vote’ papers of the political parties, the ballots and the envelopes, whole forests must have died for the election process to go ahead.

The older voters didn’t seem to share, or at least express, the same concerns. From their mouths came the oft grumbled observation that “the candidates aren’t what they used to be.” Again, a point that was hard to argue considering that the front runner in my electorate is currently charged with historical sexual offences and both major parties had vowed to ban him from parliament if he was elected. He was elected.

The one unifying factor of both the older and younger voters was the total ignorance of who they were actually voting for. They would come to my little table gripping the how to vote cards that had been handed to them at the door, but being out of their electoral district I would hand them voting ballots with a completely different set of names, most often from electorates where they no longer lived. Even the young ones, concerned with the environment as they were, didn’t seem to make the connection between voting and the environmental policies of candidates. They only asked what was the minimum they needed to do to vote (to avoid the fine). Many just folded the ballot papers up, unmarked, and handed them back to me with a “that’ll show ‘em” kind of grin.

But back to the original question. Has my time with the voters convinced me of the limits of democracy? Well, a tired incumbent Government has been voted out and for better or worse, new people with new ideas will get their chance. Somehow that seems right to me.

I am tempted to close with another quote of Churchill’s, that “Democracy is the worst form of Government – except for all the others.” But instead, I think that an old quote that has stuck with me from my days of studying political science seems more appropriate. "In a democracy people get the leaders they deserve."

*The Wallabies are Australia’s national Rugby Union team for those listening outside of Australia.

If you enjoyed this post please hit the heart button, leave a comment or share it with someone you think may enjoy it too. As always, thank you for reading.

Share this post