In 1891 Oscar Wilde, the Irish poet, playwright and author wrote in The Picture of Dorian Gray, “To get back my youth I would do anything in the world, except take exercise, get up early, or be respectable.” These days, in Australia at least, the pursuit of eternal youth has been surpassed by the pursuit of home ownership, a national dream that has morphed into a neurotic national obsession. Wilde’s line resonates as a neat summation of the tension between the things we want and what we are prepared to do to get them, though these days I am not sure there are any exceptions to what some people would do to possess their own home.

My father was born to Italian immigrants, raised in the Sydney suburb of Leichardt overlooking Balmain Bay, the only son in a family of nine daughters. They slept ten to a room and his father worked three factory jobs.

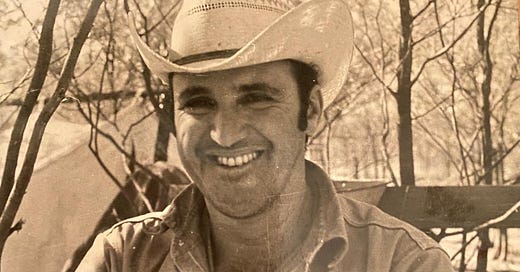

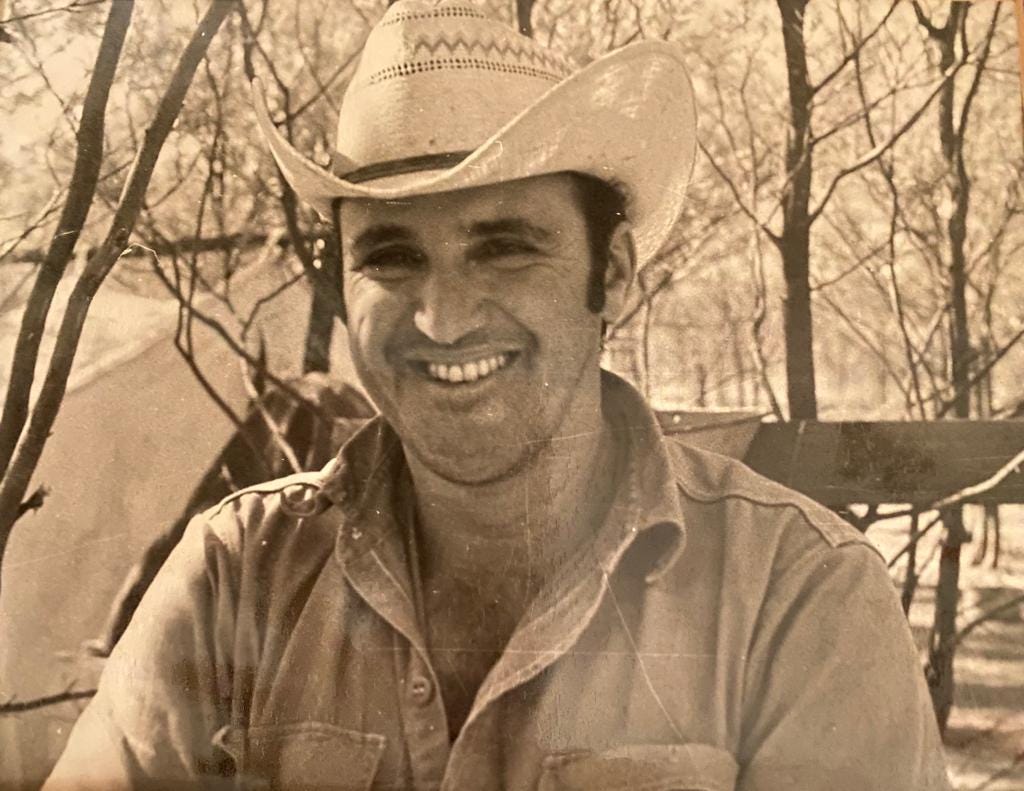

The city held no allure for my father, and he left Sydney young, and school younger still. By the mid 1950s he was working in western NSW as a boundary rider on Boorooma Station outside of Brewarrina. As the name suggests, his job was to patrol the boundaries of the property on horseback, mending fences as he went. When opal was discovered at the nearby Glengarry opal fields in the early 70s dad followed the rush there. He camped in a tent before upgrading to a tin shack. It was on the opal fields that he met my mother, herself a migrant from New Zealand. She moved out of her tent and into dad’s shack.

When my older brother reached school age dad moved the family to Mudgee, where he found work on the construction of Windermere Dam. He was employed as a powder monkey, responsible for managing the dynamite used for blasting rock. Once the dam was constructed dad relocated the family to the Hunter Valley, where he found work as a fencer. Not the kind of fencing with the neat white suits and the bendy swords, but the kind of fencing that requires post holes and fence posts.

In summer it was hard, hot, exhausting work. In winter it was hard, cold, exhausting work. He would wake before 5am every day and be home well after the sun had set. I remember him being constantly tired, even on weekends. Holidays were something that other people had. But he never stopped, he couldn’t stop, because he had a family to feed and house payments to make.

And that brings me to the part that I find most remarkable, that the son of Italian immigrants with no education to speak of, who spent his working days digging holes and filling them with fence posts was able to buy his own house. But he didn’t stop there. He then bought a second house. On the Sunshine Coast. And it took him only five or so years to pay off that second house.

Writing that sentence in 2022 feels like I am taking my writing career into the realms of speculative fiction. I still haven’t paid off my HECS debt and even in a two-income family, home ownership seemed as likely as space travel. No scratch that, space travel looked a lot more likely.

But of course, I could buy a house if I chose to. I once spoke to a bank about a home loan and was mortified when they expressed a willingness to lend me almost $2 million dollars. I was mortified because at the time I was only employed on a 12-month work contract. I ran from the loan manager’s office. I was not prepared to borrow any amount of money off an institution that was mad enough to lend me millions of dollars. And even if I were prepared to borrow that kind of money, or significantly less, I was not prepared to spend the next thirty years of my life living in fear of an interest rate rise, of redundancy, of feeling tied to a job that I dared not leave lest I couldn’t make repayments.

My father made different choices and worked himself into the ground to satisfy them. He did his best for his family. But there were times when I did not meet his return home from work with joy, but rather anxiety as I mentally checked off a long list of jobs that were expected to have been completed: had the eggs been collected? the leaves raked? or the bins taken out? And God forbid if something had not been done. Whatever Dad suffered from in those days, it went undiagnosed, and the symptoms were avoided rather than treated. There were rages, mood swings and days of silence when he would retreat to the shed and sharpen his shovels and crow bars over the hot glow of the forge.

But the trade-off was that he owned his own home. For the Italian migrant in him, and his very Italian concept of family and providing, it was a trade-off he was willing to make. But these days, even if we grind ourselves into the dirt, or the plush office carpet, and keep a beady eye on interest rates, if we sacrifice family and mental health at the alter of loan repayments, is there a guarantee that we will ever own our own home? I am not sure. So, to bastardise Oscar Wilde, I would do anything to own a house, except sacrifice family, health and wellbeing.

Dad no longer lives in the house he sacrificed so much for. Eighteen months ago we took the difficult decision to place him into aged care. I would do anything for dad to be young again. And if he did have his time again, I wonder if it would all still seem worth it, would he accept the same trade-offs, make the same decisions? It’s a moot point now. In the end his only decision was whether or not to accept the morphine offered by the nurses. During his last days, I sat by his bedside and though I’ll never know what was going through his mind as he waited for the morphine to do its tragic yet necessary work, I find it hard to believe that whatever he was thinking had anything to do with fence posts or house payments.

With special thanks to the wonderful Annabelle Hickson for providing the audio version of this week’s post.

Share this post