Something a little different this week. For the past month I have been on the book promotion circuit. I wrote the piece below as an Op-Ed but nobody wanted to place it “opposite the editorial page” or anywhere else in their newspapers for that matter. The response from one newspaper in particular may explain why:

“The story of Abdul Wade is a fascinating piece of little known history.

I feel that the racism angle is a bit obvious and that our readers will know that Australia has a long and shameful history of marginalising everyone.

Could Ryan tweak the piece so it's about Abdul's achievements and explain how he came to write this book.”

Ironically, one of the reasons I wrote The Ballad of Abdul Wade was because I felt that Australians do not know or recognise many aspects of our history, including the enormous contribution made by men like Abdul Wade despite the prejudice they suffered. I am hopeful that Australia is now ready to start hearing these stories.

I am also sharing this piece because it is a look behind the scenes of being out of office. Self promotion is a part of that, promoting my work is a part of that. If I am to make this change work these are the things I must do. Speaking to other writers and artists it is a challenge that many struggle with, how to pursue the creative life you want to live but manage to make it economically viable; how to successfully move between the creative world and the business world. It isn’t easy and it is something I am still working out.

I will write about what I have learned in later posts. But for now, I hope you enjoy this piece.

The Ballad of Abdul Wade: A Very Modern Tale

In 1902, sitting in London, Henry Lawson wrote “A bushman has always a mate to comfort him and argue with him, and work and tramp and drink with him, and lend him quids when he's hard up, and call him a b—— fool, and fight him sometimes; to abuse him to his face and defend his name behind his back; to bear false witness and perjure his soul for his sake; to lie to the girl for him if he's single, and to his wife if he's married...”

Eight years earlier, in 1894 and less than 12 months after returning from a trip to the bush, Lawson expressed a different opinion of the Australian bushman: “I could never see any sense or reason in the treatment which the Australian new chum receives and has always been subjected to at the hands of a certain class of Australian bushmen.” He goes on to describe the treatment as “ignorant brutality” before asking “Is it because they (bushmen) have a lurking, aggravating idea that he (the new chum) might be equal or superior to them in some respects – that if he does not show it, he thinks it?’

Though the first quote in many ways came to define the image of the Australian bushman, and by extension white Australia, the second seems more reflective of Australian identity, then and now.

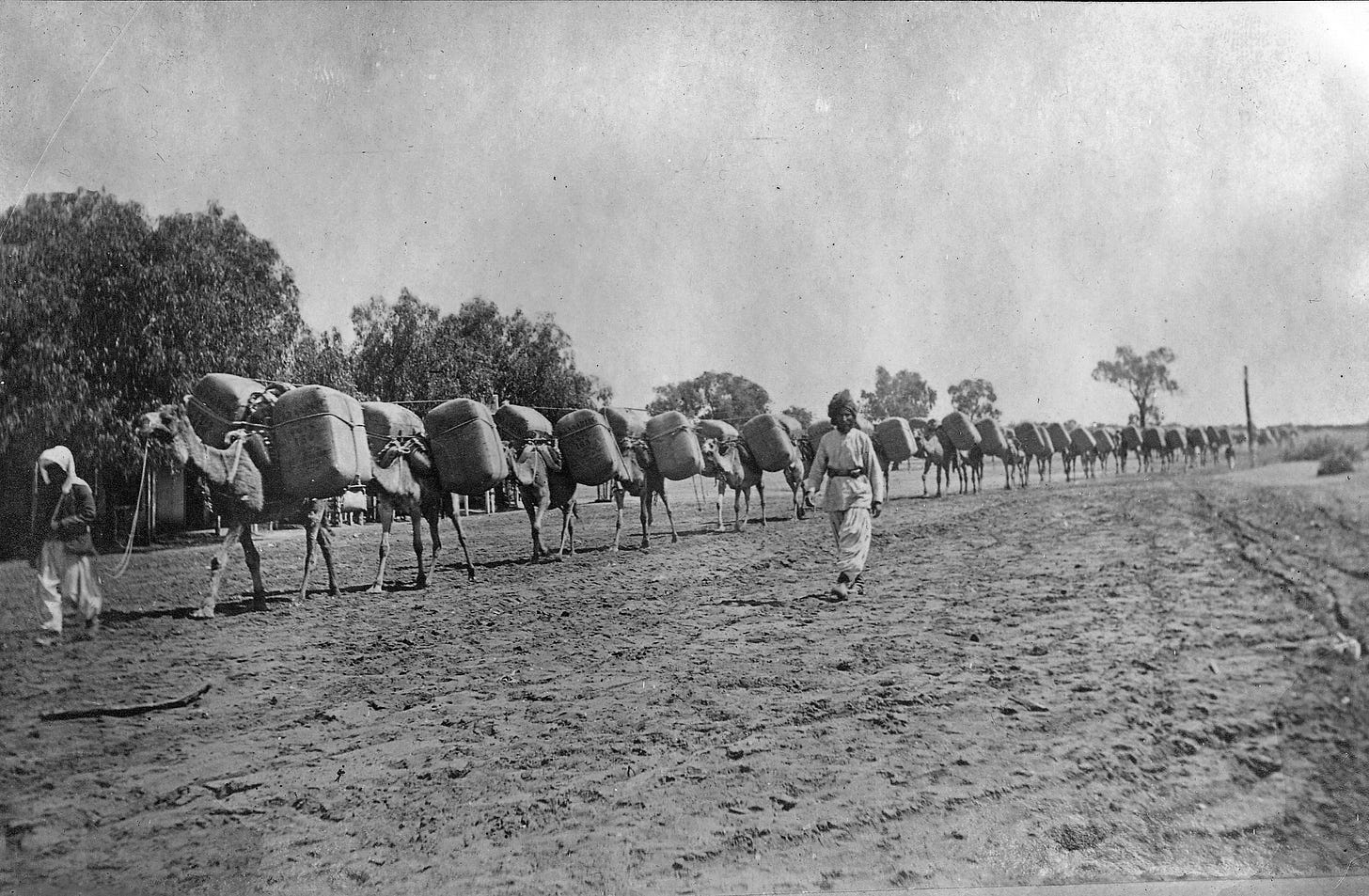

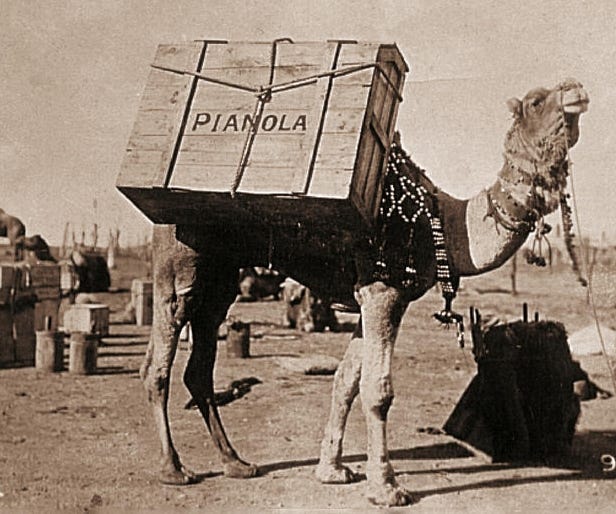

For the last four years I have researched the life of Abdul Wade, an Afghan entrepreneur, investor and grazier who migrated to Australia in 1882 as an indentured labourer and rose to dominate the Australian transport industry at the turn of the 20th century.

In his time, Abdul faced his fair share of enemies, men who held prominent roles in the public life of the young nation. But he also had his supporters, white Australians who felt, like Abdul did, that a man should not be judged upon the colour of his skin but on his contribution to society.

While the modern, English language histories of the Afghan cameleers delight in including details of the ridicule that Abdul was subjected to in Australia, most notably because of his “Afghan-ness”, very few provide a thorough account of his achievements, nor do they record the voices of his supporters. To find those, and there are many, I had to dig back into the newspapers of the day.

Abdul’s crime, apart from being wrapped in the skin he was born in, was that he worked too hard, was too successful and drove many a white competitor out of business. He was outspoken and a gifted networker who built a place for himself among the elite of the Australian pastoral industry. His business partners included the famous pastoral company, Dalgety & Co. and ex-Queensland Premier Sir Robert Philp. He owned a waterside mansion in Lane Cove and extensive pastoral holdings in western New South Wales.

Whereas Abdul’s biographies omitted his achievements, the biographies of his chief antagonists have omitted their xenophobic activities. I am thinking here of Senator Edward Millen, one time Minister of Defence and Thomas Waddell, ex-NSW Premier, albeit for a short few months. Millen and Waddell founded the Anti-Alien Labour Movement in NSW and agitated for the removal of all Afghans from the colony. Their lobbying laid the groundwork for the NSW Immigration Restriction Act of 1898, itself a step towards the Federal Immigration Restriction Act, the infamous white Australia policy.

In the early 1890s, both Millen and Waddell urged the residents of NSW to take the law into their own hands if Parliament would not make laws to ban Afghans from NSW. The message was “We will decide who comes to our shores.” It all sounds very modern.

And that is the point. If we cannot look honestly at our history, blow up the myths that have served as pillars of a delusional national psyche, the mistakes of the past become the mistakes of today. Yet I sense a national reticence to unearth our many alternate histories and where necessary correct the record. Is white Australia scared of what we will find? Afraid to discover that people who don’t look like us, speak like us, think like us, pray like us, drink like us are, as Henry Lawson noted, indeed a little better than us?

If we fail to acknowledge the true achievements of men like Abdul Wade whilst simultaneously ignoring the bigotry and race-baiting of men like Millen and Waddell, then as a nation we are nothing but denialists, with little hope of building a more equitable nation for those that were here, are here and will be here.

We cannot continue to deny our history and hold tight to myths that have become stale impediments to national advancement. We can no longer dismiss the need for examination with a trite, “that’s just the way things were back then.” Australian history needs to be set on fire. We should do it confidently, urgently and collectively. After the blaze, green shoots will appear as they always do, and they might just look like truth and reconciliation.

If you have enjoyed this post please give it a like, share it or leave a comment. I would love to hear from anybody who has already read the book. And if The Ballad of Abdul Wade sounds like it is just your thing then you can purchase it here or in all good bookstores and online. For those outside of Australia you can purchase on Amazon Kindle. As always, thanks for reading.

I always listen to your posts at the end of a long day--pacing up and down my driveway. There’s always so much to think about and ruminate on after each listen. You’re doing wonderful work. Keep it going!

Also, fun fact-- One of my aunts is an Australian citizen but her son is a Kiwi. My Kiwi cousin married a Spaniard with German ancestry and they’re living in Hong Kong.

I’ve lived in India, the UK, the US, and now in Canada. Each place I’ve seen the good and the bad. Almost always, the spirit of goodness and kindness wins.

That photo of the camel with the pianola - brilliant. Loved this piece